Corona’s surprising effect on an evening at the theater

My favorite small theater has reopened after months of lockdown and we are attending a two-woman show called Primacomedy. I return here with mixed feelings. Would it be full? How will they deal with the social distancing inside the theater?

I enter – and gasp. The usual 50-plus seats have been whittled down to just 20, and half of those are empty. When the performance begins, I count just 11 spectators. It feels like a giant living room.

This tiny cultural venue in Munich, the Pasinger Fabrik, is housed on the premises of an old factory that looks very unassuming from the outside, nearly obscured by a wall of solar panels. Its white walls have unidentifiable pipes emerging here and there which once served a purpose but have long since found a new life as industrial decorations.

Once inside, the building’s magic is slowly revealed. An architectural version of Mary Poppins’ bottomless carpet bag, glass doors, windows, oddly located staircases and varying floor levels lend the building a labyrinthine air. If you walked through the whole place, you’d find a restaurant, a bar, several small theaters and rooms where children learn to sing, paint, speak English or learn carpentry. It feels like something that Jules Verne would have built if he’d been into cultural events and children’s education.

During normal times, the theaters are full, as is the restaurant which audience members frequent before or after a performance. You can normally see them meandering back and forth along the edge of the atrium of the restaurant to get to the theaters. The whole building is abuzz.

But these are not normal times. Here we are – with barely enough people to play a game of basketball. That means there was a performer/audience ratio of just 1:3, counting the sound effects guy. “These poor women,” I think, “performing to a nearly empty room. All that work for a room that is practically empty. This is going to be an excruciating, embarrassing evening.” You may ask why I even bought tickets, and the answer is that secondhand embarrassment is still better than boredom.

I couldn’t be more mistaken. I am about to experience the most unusual theater performance of my life.

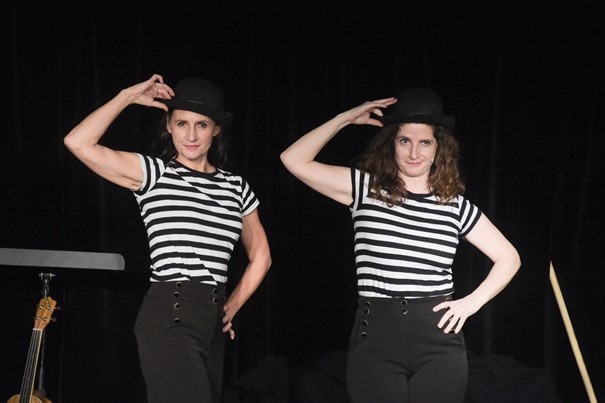

The two-woman show performed by Nadia Tamborrini and Bele Turba consists of sketches, songs and dances. One sketch features an aspect of the German language that everyone loves to poke fun at, Beamtendeutsch, literally “civil servant German.” This is a language unto itself, and its speakers – in this case a police officer reporting from a crime scene – utter things like this:

For the rescue services that were summoned to the scene, the following picture has emerged: The presumably injured person was in the process of visiting a gastronomic establishment for the purpose of food and drink intake and whereupon said subject seriously injured by the suspected perpetrator by means of the placement of said perpetrator’s fist in the face of the presumably injured person.

The original is even wackier, delivered in lilting Bavarian dialect.

This performance gets us all laughing.

Then Tamborrini receives a pretend call from her Italian mother.

“Hai mangato?” Have you eaten?

“Mamma, I’m in the middle of a spectacolo!” she responds. Then mamma wants to know if her partner has eaten, too, and they have a brief conversazione. She hangs up, revealing that she speaks no Italian. No problemo.

Then comes the customer service help desk, and the “customer” starts by giving the serial number of a broken DVD player. She subsequently gets rerouted through a half-dozen people, each with a different accent, each one progressively less intelligible than the last. Inevitably, she winds up back where she started. And the DVD player is still broken.

But it is the encore that transforms the audience.

“A song or a text?” Turba asks the spectators.

“A dance!” a woman in front shouts. Everyone chimes in. “Yes, a dance!”

“It’s the song we already played – but this time you have to dance, too!” she replies.

The soundman puts on a conglomeration of ’60s and ‘70s hits, each clip corresponding to its own dance from the respective era.

The woman in front jumps up from her seat, rips off her jacket and starts to dance.

Two more women leap to their feet, joining in. Before I know it, I am up and moving to the music, too.

But the coup de grâce is when my husband gets up and starts doing The Bump with me – this from a man who won’t even do the wave in a baseball stadium. (Granted, we don’t have any of those in Germany. But if there was one and they did one, he wouldn’t.).

Everyone is dancing! We have all left our seats and have turned the theater into a disco (I mean, dance club, oops, getting carried away with this ‘70s lingo). Now it’s no holds barred. Everyone twists to Chubby Checker, lines up for the BeeGees’ Staying Alive and does the camel walk, which I had danced before but didn’t realize until now, decades later, that it had a name.

On stage, Turba and Tamborrini can hardly believe their eyes. They never stop moving but can’t help gaping at the audience that has stolen the show. Their show. Not that they mind. They’re enjoying it almost as much as we are – but just almost. We are all twisting, laughing and gyrating to the rest of the medley, weaving amongst each other throughout the room.

The music ends. The spell is broken.

As we walk out, I exchange verbal high-fives with the dancing ladies of the front row. Exhilarated, breathless and sweaty we exit from the magical theater where we, a handful of spectators, turned the evening into our own performance.

I look at the people, mingling outside in the restaurant looking very normal, and smile smugly at them. Ha! They have no idea what they just missed.

Brenda Arnold

Title photo credit: Primacomedy

It’s heartwarming, especially in a pandemic time like this.

I agree! We have to hold on to these kinds of experiences

I totally agree with Andy. You should call it “Pasing 11” 😎

OK, I give up – what does “Pasing 11” mean – do you mean like “Ocean’s 11”?

Exactly! You got it 👍

Rare experiences like this are what make living life special

I totally agree! And you really never know when something like that is going to happen